Looking back, 1977 was a key year for me. I didn’t rocket to fame, I didn’t take British culture by storm – though I’m sure those were the dreams I was having at the time. What I did in ’77 was to stage a play with a local amateur company (a talented bunch who deserved better material, if I’m honest), sell my first radio drama, and see my first book in print (a novelisation of said radio piece).

Looking back, 1977 was a key year for me. I didn’t rocket to fame, I didn’t take British culture by storm – though I’m sure those were the dreams I was having at the time. What I did in ’77 was to stage a play with a local amateur company (a talented bunch who deserved better material, if I’m honest), sell my first radio drama, and see my first book in print (a novelisation of said radio piece).

With all that going on, I thought I was the bee’s nuts. I imagined I could do anything. In retrospect I was no shooting star, and in retrospect I’m grateful for that. I was getting the thing I didn’t know I wanted; grounding for a sustainable career based in diversity. I’ve seen writers of my generation have a hit and disappear, or spend the rest of their careers struggling to match it, or be stuck repeating themselves until death offers a release.

For me, a different pattern emerged. I’d have a great year, then a shit year, then I’d reinvent the wheel. It’s as bumpy as the Indiana Jones ride at Disneyland, and fun in the same rough hazards-and-surprises kind of way.

In ’77, I was going to write a musical. It was going to be about Doug Fairbanks and Mary Pickford, about the glory of silent cinema and the birth of superstardom, about the formation of United Artists and the end of an era with the coming of sound.

I know with the success of The Artist it’s trendy to say so, but I’ve always loved silent film. From before the Thames Silents presentations, before Michael Bentine’s Golden Silents on the BBC, all the way back at least to Bob Monkhouse’s Mad Movies, intelligently presented from his own collection. The only Oscar I’ve ever held was Robert Youngson’s, for The Days of Thrills and Laughter. Monkhouse was the real deal as a collector but I once had a modest collection of my own, starting in childhood with a 50′ clip of Chaplin’s Easy Street that came with a second-hand tinplate projector from Shawcross’s of Eccles, local auction house and Aladdin’s Cave.

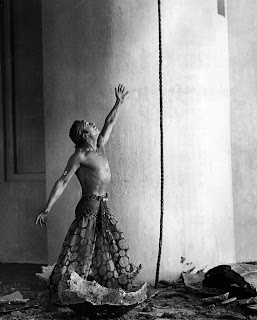

As a teen I’d wash cars and blow my savings on Super 8 prints of the classics; my first and most-wanted was Metropolis, my most-watched were the Fairbanks costume spectaculars – Robin Hood, The Mark of Zorro, The Black Pirate – every one of them a veritable foundation document for a different action genre. The Blackhawk catalogue, Thunderbird Films, Perrys of Wimbledon, Derann of Dudley – these were the dealers of my dreams.

As a teen I’d wash cars and blow my savings on Super 8 prints of the classics; my first and most-wanted was Metropolis, my most-watched were the Fairbanks costume spectaculars – Robin Hood, The Mark of Zorro, The Black Pirate – every one of them a veritable foundation document for a different action genre. The Blackhawk catalogue, Thunderbird Films, Perrys of Wimbledon, Derann of Dudley – these were the dealers of my dreams.

I had special affection for Blackhawk’s The Thief of Bagdad, which I’d run with the accompanying piano improv soundtrack by Florence de Jong and Ena Baga. The music was recorded during a screening at the Academy One cinema, and issued on vinyl. I was going to add “issued on vinyl for geeks like me” but I was a dabbler, really, compared to some. I’ve an awful suspicion that my love for any subject is determined by the extent to which I can steal from it.

So in ’77, heady with a droplet of success and firm in the delusion that I could tackle anything under the sun, I set my sights on Doug and Mary.

He was Hollywood’s biggest male star, and she was “America’s Sweetheart”. Fairbanks was a graceful athlete of spontaneous creative instincts combined with great determination, while Pickford was as clearsighted in business as she was vulnerable onscreen. Their romance was genuine, their partnership golden, its ending a sad disengagement. There was a shape there; the key would be to find a theme.

In the late 70s Doug’s only son, Douglas Fairbanks Jr, was living in London’s Mayfair. It has to be tough following in the footsteps of such an iconic father but Douglas Jr had made his own mark, first with (in his words) “big roles in little pictures, and little roles in big pictures” and then, following distinguished war service, some big roles in big pictures and an active role in early international TV production. With all the confidence of an upstart, I wrote to him.

(By which I mean I wrote him a proper letter, not its modern, mass-emailed, hey-you-you’re-famous-so-help-me-out equivalent.)

He wrote back, generously and at length, and more than once.

13th June, 1977.

Dear Mr Gallagher

Thank you very much for your courtesy in writing and I am proud and delighted that you would want to write something about my father’s career.

However, I do want to warn you that the idea had already occurred to two or three other people over the past fifteen or twenty years, and even though they have been well-known playwrights and theatre people the projects have come to nothing because, except for a couple of domestic problems, my father’s life per se was not sufficently dramatic to justify a play. His career was indeed spectacular and he was unquestionably a great creative artist and producer but beyond that the material is not rich enough to sustain a complete play. Any detailing of domestic sidelights would be likely to lead to complications as some of the people are still living – such as my step-mother.

I have no personal objection to your trying to write such a play but I thought it only fair to warn you that others had come to a dead end working on the same idea. There have been two recent books about my father which I would recommend to your attention: “DOUGLAS FAIRBANKS, THE FIRST CELEBRITY” and “THE FAIRBANKS ALBUM”, both by Richard Schickel. These are both well researched and accurate and make interesting reading but I do think they would be difficult to dramatize. The most theatrical part of my father’s life was on the screen rather than off.

Yours sincerely

Douglas Fairbanks

The hair rises slightly on the back of my neck as I read the reference to “my step-mother” – Mary Pickford was still living at the time, and stayed with us until the end of the decade.

As it happened I’d read the first of the Schickel books under its American title of His Picture in the Papers. I didn’t keep copies of my own end of the correspondence, so I can’t say what impression I was making. But I must have communicated at least some of my enthusiasm.

I mean, just look at this.

23rd June, 1977.

Dear Mr Gallagher,

I was most interested in your kind and informative reply to my letter and I will be most interested to follow your progress in your intended dramatization.I must however invite your attention the fact that the “decline” of the careers of certain film artists after 1930 was due to a number of different reasons – unique to each individual – and not because of the problem of the market no longer providing the suitable outlet you refer to.

In the case of D. W. Griffith, for example, his own decline as a director began several years before that and had really nothing to do with either the advent of sound or the changes in corporate interests. It was merely that this very great talent had burnt itself out and his films, even in the middle 20s when he continued to have a free hand and satisfactory budgets, no longer enjoyed either public or critical support. The situation, despite everyone’s goodwill, became too expensive and risky to go along with and no one appreciated this fact more than Griffith himself. Consequently the other partners of United Artists covered for him as best they could and he eventually retired from that association.

Keaton on the other hand was quite another “cup of tea” in so far as he had never really been completely his own master in terms of production and distribution. He was recognized within the profession as being one of the most gifted and original of all comedians but he was never too interested in business per se. Even when his silent films had begun to slump and he associated himself with Joseph Schenck (as a result of his marrying the sister of Norma Talmadge, who was then Mrs Schenck) in order that the burden of production would not fall on him, this did not work out. The introduction of sound films may have made some difference in the end, but it was not really the main problem, which was somewhat like that of Griffith in so far as the public no longer supported him in the way that they once had, and his prestige and drawing power- even at its height – could not compete with Chaplin’s. It is only now in retrospect that we realize that he was actually in many ways Chaplin’s equal as a mime, but it was not as fully appreciated then as it is now.

The case of my father and Chaplin was something else again. It was not that their careers “declined” because of the need to “reshape their careers” nor to the introduction of corporate interests entering the field. It was largely due to the fact that both Chaplin and my father had believed that their best medium was the purely pictorial or visual form of story-telling and that they did not really want to introduce or participate in sound films themselves. When they did so it was due almost entirely to their obligations to the company they had formed together, and they took relatively little interest and had little enthusiasm for what they did so long as they were meeting their responsibilities as partners. They had no objection to sound films made by others, and in fact enjoyed them immensely, but they did not really want to even try for themselves. Both Chaplin and my father had hoped to avoid the responsibility of making more films unless they were silent but could not do so and had to alter the original concept of United Artists and bring in others who would supply enough production to maintain the overhead costs of their distribution organizations. It was less them but more my stepmother, Mary Pickford, who actually went out and sought others to join United Artists – such as Joseph Schenck (mentioned above), who also later brought in Daryll Zanuck and later Samuel Goldwyn. But the short answer is that they were all professionally “tired” and preferred to let the original United Artists concept be altered, and hence gradually pulled out of production altogether. There was no real drive or wish to continue their careers as such because in fact they had none of them suffered any very severe reverses. They just lost interest and evolved a plan to expand their corporation so that they could “slide out” of their obligations and let others “carry the ball”. Miss Pickford was the only one who really wanted to continue and so the various changes that took place over the next ten or more years at United Artists were usually opposed by her and she was the last one to sell out her shares. I know very well that my father could have – had he wanted to – continued to produce films of the same quality and of the same standard as before, but he quite openly admitted that he no longer had any desire or wish to.

The proof of my statement lies in the way he practically “cheated” in the making of his last few films. “Round the World in 80 Minutes” came about only as a result of putting together his films of a world tour he made – originally intended for a private record and later, when he realized that he must deliver something, he added some linking sequences on his return and put it out as if it had been planned that way from the first. Mr. Robinson Crusoe was never “planned” but came about as a result of a yachting cruise he made with some companions in the Pacific and, when they arrived in Tahiti and again he faced pressures from his partners and the distribution organization repeated its demands, he decided to use the cruise as the basis for a film. It was made in a relatively haphazard way and as a result of a snap decision to do something. Once again, additional scenes were made later upon his return and he was glad to be done with it. “Reaching for the Moon” and “Don Juan” commanded so little interest and enthusiasm from him and he was so wrapped up with other matters in his private life that he, for the first time since his first year in films, delegated practically all of the responsibility for production to others, managing thereby to divest himself of the chores he once enjoyed and to honour the agreement with his partners with the least trouble to himself.

In other words, what I am trying to suggest is that in these latter cases it was not that their careers declined for the reasons you suggest but because they had run out of ideas, used up their energies and really did not wish to adapt themselves to changes in the medium. They were delighted when new partners were brought in and they could sit back and let others carry the load that they had originally carried.

I trust the above will be of some interest and use to you as it is in fact a matter of record as to what happened.

Toward the end of the year Fairbanks went to Australia, touring his stage production of The Pleasure of His Company, but he took the trouble to have his assistant update me with his New York address for correspondence after the tour.

The last letter I have came from the Town House in Adelaide in the November of that year. I’d been telling him of some of the material that his advice had led me to, and he wrote:

I was most interested to read of the progress you have made wading through all that very dated and often unreliable material… X’s book is, as you suggest, a very good one in many ways and indeed it is one of the best although even here I have found numerous errors, some trivial and some serious. It is so awfully hard to be certain about anything concerned with such a self-disguising industry as the Motion Picture Industry.

With the best of wishes.

I am,

Sincerely,

DOUGLAS FAIRBANKS JNR.

It pretty much ended there because he’d been right from the beginning; despite my fascination with the subject, in the end I couldn’t crack it.

But what a gentleman. I can only hope I showed an adequate appreciation of his kindness.

4 responses to “The Movies, Mr Fairbanks, and Me”

My own, less personal, remembrance of Douglas Fairbanks, Jr comes from 1987 when he briefly visited Chipping Norton as a guest at Tracy Ward's wedding. My family trouped down to the church to see the big TV star, and when my great aunt, a woman of a certain age, clapped eyes on Mr Fairbanks, she instantly became a fluttering fan girl. That was a big day for our little town!

Regarding Silent Movies, I was turned onto them by Kevin Brownlow's Film Four Silents at Sadler's Wells, particularly The Wedding March and The Iron Mask, Fairbanks senior's final silent film. Amazing events. I then went out and got my hands on Brownlow's The Parade's Gone By, which is a hell of a book. It's such a shame so many films, and careers, are now lost and forgotten.

Hi, Lee, it's been a while.

I have to say, THE PARADE'S GONE BY is my desert island book. And Brownlow's HOLLYWOOD documentary series is long overdue a repeat.

I'm currently reading Lillian Gish's autobiography, hence the title of the post.

I also share your love of the silents and, as a kid, probably had the same Super 8 collection as you!

I envy the silent film makers in Hollywood the excitement of being pioneers in a sunny new land. But something else in your blog strikes me too.

Letters are a very intimate form of communication compared to e-mails. It was also the carefully worded and thought-out letters of advice which I received from the "greats" that helped me when starting my career.

If you'd had a quick e-mail back from Doug Fairbanks Jr saying, "Others have tried/ failed. Sorry. Try these few books. Doug"; it wouldn't have had the same resonance in your life. A sobering lesson (hard copy to follow in post!)

And the 'greats' are probably on their guard more, now that they're relatively accessible to large numbers of people who don't so much want to engage, as feel entitled to a hand up.