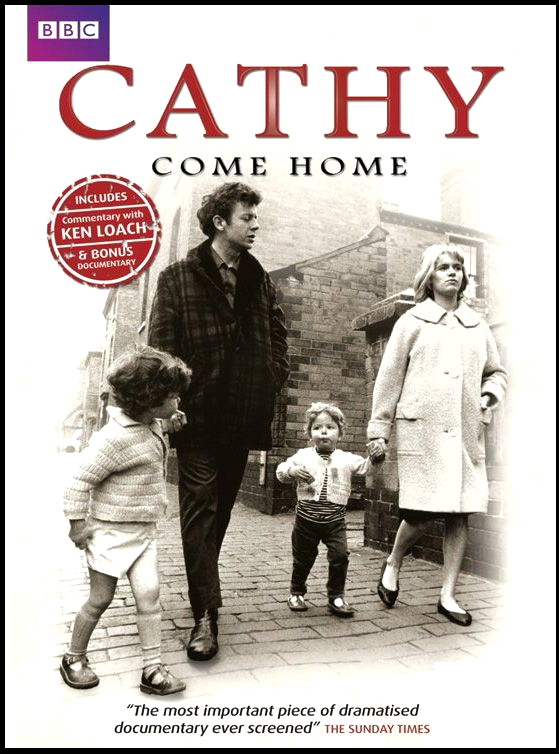

Through the 60s and into the 70s, the single play was regarded as apex TV. Though I was mainly a series-addicted kid I did see a few of them, my most vivid of those early memories being of the first broadcast of Cathy Come Home. Back then there were just the three channels and you watched with your parents, but as an only child I was included in their viewing choices as often as they conceded to mine. With Cathy I think they were affected by the social message while 12-year-old me’s takeaway was of the radical technique. Still art, but unvarnished and truthful. Years later when there was a vogue in drama for faux-naif camera shake I’d find myself thinking, “Oh, FFS, just point it and shoot”. But I always felt that the single play slots were TV for the grownups, of which I was not one, and even now that feeling’s never quite gone away.

Maybe that’s because as I reached maturity the focus shifted from multi-camera studio drama to more Cathy-style TV movies. David Hare’s recently been mourning the shift, though you didn’t hear him complaining while his stuff was still being commissioned. Personally I always thought studio drama was a fudged form; theatre dressed up to look like cinema, mimicking the visual grammar with a compromised toolkit. You’d get a rare piece that would fly along and make you forget (Ghostwatch, Screen One’s most-watched entry, scored by subverting those very techniques), but mostly you were making unconscious allowances. Now when I look at archive TV the allowances are conscious.

There’s something I remember from Colin Welland. He was looking back to a time in the development of Chariots of Fire when the movie finance wasn’t coming together and it looked as if they might be making it for television; despite having ‘come up’ through TV himself he’d little enthusiasm for the prospect because, as he expressed it, instead of showing events the drama would become ‘conversations about events’.

But at least the commissioners of single play slots were open to experimentation, which along with Ghostwatch led to some memorable telefantasy from the likes of Rudkin, Pirie et al. I entered the industry just as executive culture seemed to turn against genre material. Which puzzles me still, because as the relaunched Doctor Who showed, telefantasy is one of the few forms that can bring together the much sought after ‘family audience’. Producers and production companies were always up for it, but we were met with an attitude that saw genre material as suspect and embarrassing despite its popularity globally and across other media.

The Broadcast Act of 1990 had made things worse by concentrating commissioning power in fewer hands; where once you could pitch your wares around a number of ITV companies now there was just one portal for the entire network. The credo was that there was an ‘ITV viewer’ whose interest was in ‘people like us’ storytelling. A view heavily influenced, I suspect, by the audiences for the soaps. The BBC reorganised so that channel controllers had decision making power over drama; I developed a big miniseries project called Victorian Gothic with Jane Tranter’s department only for the then-controller, who I believe came up from BBC Sport, to run the clock out on the deal.

I got a few things through but after every success it was like I then had to reinvent the wheel. Chimera only happened because a deal fell through leaving Anglia with four network drama hours to fill, and they remembered the oven-ready show they’d rejected a few weeks before. Oktober was developed for BBC2 and another example of a channel controller ghosting their own drama department. I took it to ITV where the legend is that Jenny Reeks fished the script out of Nick Elliot’s wastepaper bin and made him greenlight it. When Lawrence Gordon Clark and I put together the Chiller anthology series we were told by YTV’s Vernon Lawrence that horror on TV wouldn’t work; after a debut figure somewhere around 11.5m he sought Lawrence out and apologised. Then when he moved over to the Network Centre he passed over our second season.

I reckon Doctor Who only broke the pattern because there were low expectations for it, so it was shunted off to Cardiff and not interfered with. Afterwards you couldn’t move in the BBC without someone telling you how long and hard they’d personally fought to bring it back.