Adapting is not a matter of reformatting. Adaptation is re-imagination. When you’re reading prose, the incidents may run as vividly in your head as when you’re watching a movie, but don’t let that mislead you into thinking that there can’t be that much difference between them.

Back in 1997, Pumpkin Books published the full text of Dracula: or, the Un-Dead, the first-ever stage adaptation of Stoker’s novel. Performed once-only in a bare-stage reading with the sole purpose of securing theatrical copyright protection, it was a cut-and-paste, prose-into-playtext version with no concession to theatricality. As a historical document, it’s fascinating; but viewing it as drama, it’s hard to disagree with Henry Irving’s back-of-the-stalls opinion of “Dreadful.”

It doesn’t work. It doesn’t play.

It doesn’t offer an equivalent experience in the target medium. And that, really, is what it’s all about.

True adaptation is neither for the inexperienced nor the faint-hearted. Like Richard Gordon’s Sir Lancelot Spratt, you have to be ready to make a huge incision and then dive in with both hands. You have to absorb the book and try to get inside the author’s thinking, trying to get a sense in your bones of what he or she was gripped by and reaching for.

In the end it comes down to two raw materials. Impulse, and image.

These were the things that came before the prose. By impulse I mean the shape, the feel of the thing. Its tone, its purpose, its play on the emotions. And by image I mean the elements through which all those vague components are externalised. Images are those things that stay in your head when you’ve forgotten the plot. And often they’re the things that are in the author’s head before the plot gets worked around them. How many times have you read an author saying something like, “I got this idea in my mind of a man walking down a dusty road with a saddle over his shoulder, and I wanted to know who he was, where he’d come from, where he was going…”

Images aren’t so much pictures, as key moments. William Goldman (Adventures in the Screen Trade) recommends finding the five most important ones in a story and charting everything else around them. Sometimes you’ll be able to take material from the book in order to do that, a lot of the time you’ll find yourself inventing stuff in the spirit of the book. You need a structure that works for the screen, you need a narrative progression that can be rendered in terms of things you see and sounds you hear because, let’s face it, that’s what a movie is.

Adaptation means absorbing the author’s work and then getting into the author’s shoes and then doing the job anew. And all your moment-by-moment decisions have to be made in the light of the new and radically different medium that you’re now serving. You can’t blame the book if you go wrong. You’re the captain, now.

Your assets? Cineliteracy, for one. Believe it or not, film history did not begin with George Lucas. Conciseness, for another. The best story points are the ones that the viewers pick up without being told directly, the implications they see in some well-chosen piece of dramatic business. Some writers never get this. Few things can make a viewer lose the will to live more than a scene with two people in a room, sitting there and explaining the plot to each other.

A sense of pace won’t go amiss, either. Film pacing is all about compression and omission. Goldman again: get into a scene late, get out of it early. The beauty of film narrative is that you can run parallel streams of action and, by cutting between them, maintain the illusion of real time without actually sticking to it. Get that dynamic into your head, and the ‘secret’ of screenwriting moves to within your reach.

And lastly, never admit to this, but a little sense of poetry does no harm either. Kong on top of the Empire State Building is something more resonant than just a monkey on a roof. The grace note of Claude Rains and Humphrey Bogart walking off into the fog is not just there to show you what the weather’s like in Casablanca.

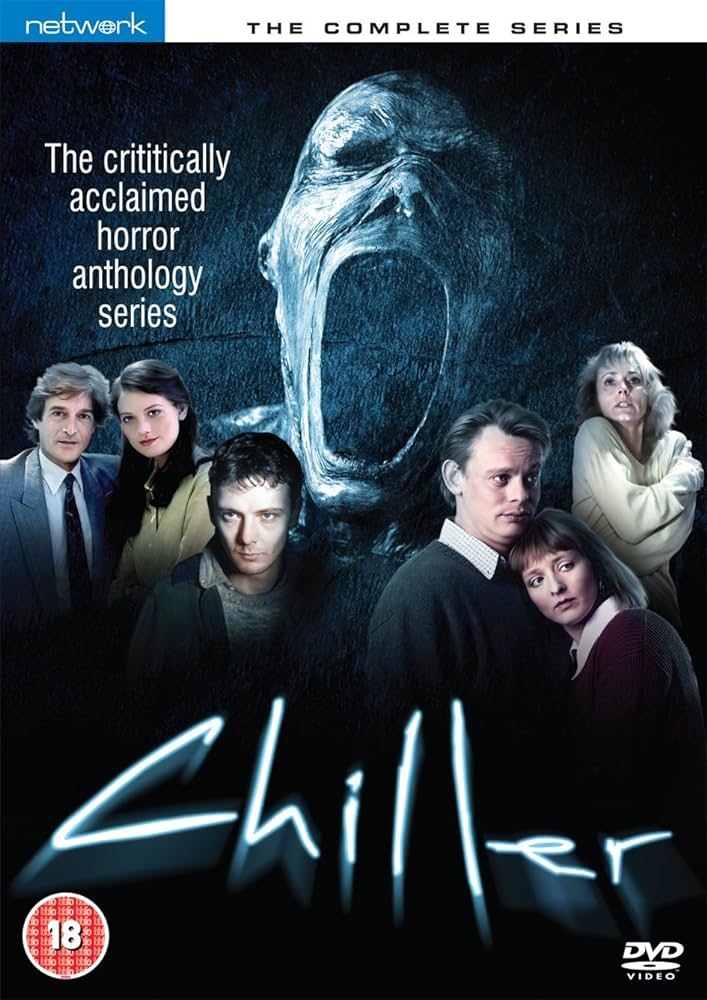

Adaptation is not an easy option, although I have to say that it does spare you the agony and brow-sweat of dragging something out of thin air where there was nothing before. Back in the day I had great fun adapting Peter James’ Prophecy for ITV’s Chiller anthology series. Peter had done all the work of the imagination; I took all his work on board and then applied invention to render it as film. On one level I changed everything, but it a more important sense I changed nothing at all… I was conscious of the responsibility to show you what was already there, but in a different way.

Peter still talks to me, so I must have done something right. There’s another discussion to be had, about adaptations that plunder and then wilfully misrepresent their source material in order to serve someone else’s creative agenda… but, what do you know? I’ve used up all my space.

First published in the Writers’ Guild Newsletter