It’s over two decades now since I pitched a new take on Dracula to the BBC, secured the commission, wrote the script, and saw the entire project canned on the very day I delivered it due to (I was told) a Drama exec’s capricious decision after lunch with an indie producer who hinted at a competing project.

Why write about this now, and not for the first time? Because I have no problem keeping a twenty-year-old gripe going, is why.

And also because I came across my foundation document while curating some of my older backups and got riled-up all over again.

Here’s how I pitched it then:

My original impulse when contemplating a new take on this was, “Nobody’s ever told the story from Dracula’s point of view.” Apart from the opening chapters covered in Jonathan Harker’s journal, Dracula spends almost the entire novel as an offstage presence. The biggest and boldest addition will be to fill in his offstage life and crimes and progress.

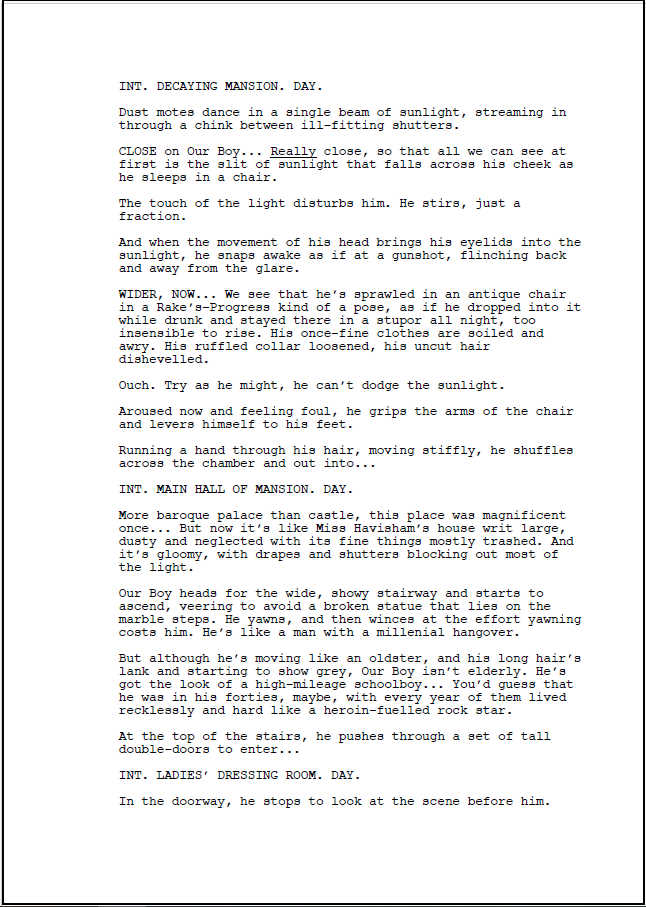

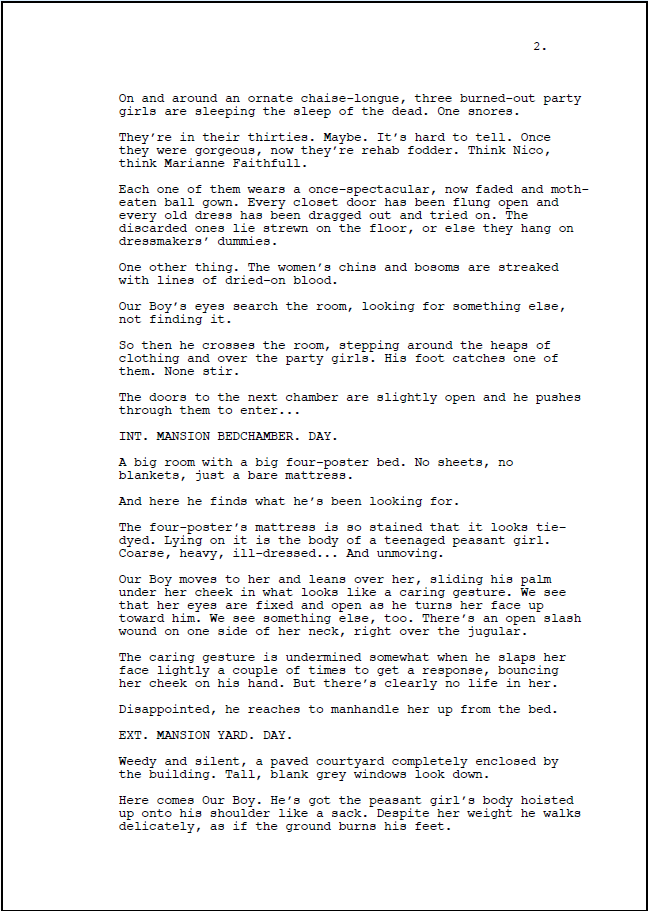

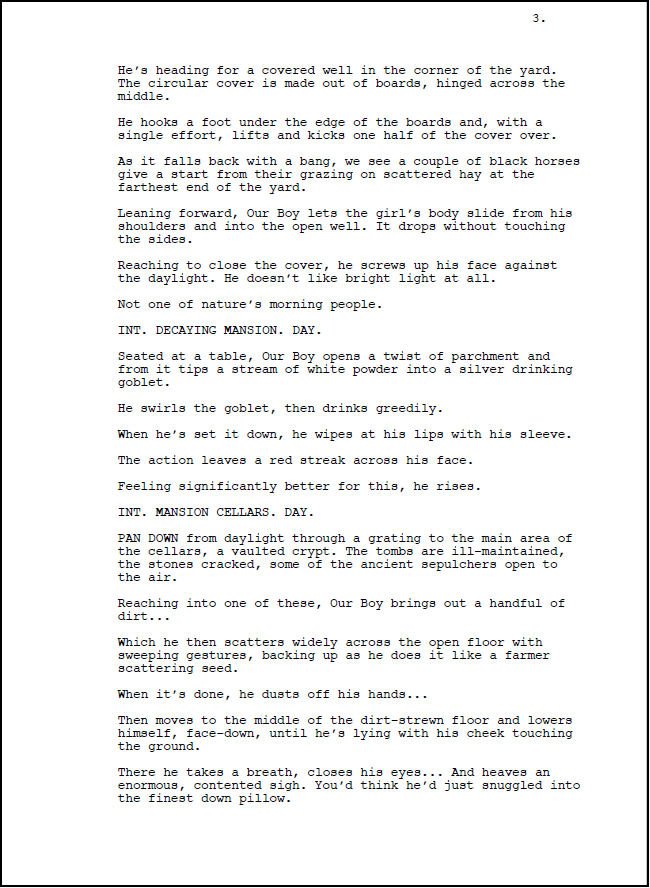

I’m put in mind of the portrayal of a modern teenaged Nosferatu in George Romero’s MARTIN. The elements I think we can take from that are the non-judgmental view of the functional vampire, and the almost forensic dissection of how his obsession works, delivering the full range of vampire shivers without at first violating our real-world awareness. Hold back the stuff about sprouting fangs and shape-shifting… what we see is a scary aristo who spreads dirt on the floor and then sleeps on it, keeps one fingernail sharpened to open the veins of his victims… he’s the junkie kid who stripped the ancestral home and blew the family fortune, last in a degenerate line, with no servants and just a few burned-out party girls left in the castle (they look more like Ingrid Pitt now than Ingrid Pitt then)… he has to wrap himself up in scarves to be his own coachman when Harker needs collecting from the village, and he has to prepare Harker’s meals and make up the beds himself (all in Stoker)… he tries to hide the fact, but not very well. He’s a lousy cook and an eccentric host. He can walk abroad in the village in daylight but the villagers all stop what they’re doing until he’s gone, and the fact that they despise him is palpable… but they’re serfs and he essentially owns them, so it’s a kind of burning, resentful stalemate, as if Johnny Rotten had bought Uist and started to run the place down.

But… our boy has hatched a plan. Seeing no future but an ever downward-spiralling one, he believes that he can turn everything around and make a new start in London, heart of an empire and capital of the world. It’s not that he intends to clean up his act or change his ways. It’s more that he reckons he can there live the life he deserves. He can fart through silk. His vast Carpathian estates are inaccessible wealth; by liquidating them he can reinvent himself as an exotic, sophisticated, upmarket figure, moving in elevated society while indulging his vices in private. The problem with his homeland is one of hypocrisy. There isn’t any. He’s known for exactly what he is, and so can never change his situation. There, he’s the morally bankrupt bastard who owns the law. But in London, with a manicure and a new tailor and with hints of his great wealth and noble ancestry in distant lands, he can put the ‘o’ back into Count.

But everywhere you go, you always take the weather with you. So while his outer image changes and he presents a sleeker, more urbane image to London society (as in Stoker), it’s all surface. He’s now a junkie at the Ritz. His base appetites remain unchanged and are a constant threat to the stability of his new life. London society doesn’t make him a better person. His presence makes London a worse place. It’s hard work, keeping it all going, ensuring it doesn’t all blow up in his face. His entire existence is crisis management. He thinks he’s winning. But all that’s happened is, he’s moved the party to some new place that hasn’t been trashed yet.

When Harker and co start to organise against him, he sees them as the one credible threat to his future and moves to pick them off. And when he can’t pick them off, he goes for their most vulnerable spot, the women. Only now does the supernatural really start to bite, if you’ll pardon the expression… up until now we could have been watching a psychotic whose actions had both a symbolic and a real-world interpretation, but now the symbolic and the real fuse. When Doctor Van Helsing asserts that Dracula is the undead, Harker and co. exchange glances behind his back. It’s Dracula’s actions that make believers of them. The dead can walk. Lucy becomes another of his burned-out party girls… her body walks but her soul is out there, somewhere, calling helplessly.

They’re hunting him, he’s hunting them. Cat and mouse. Day of the Jackal. Much has been made in recent years of vampirism as an AIDS metaphor, and I don’t subscribe to it. The major fear on which DRACULA plays is the debauchment of our loved ones while they’re just out of our reach.

We’d opened a conversation with Vincent Cassell’s people when news of our ditching came through. My producer urged BBC Wales, our commissioning body, to get out a press release to protect our project. But the indie got their announcement out that week and, in my producer’s words, effectively bombed our boat. Irony of ironies, theirs did get made but years later, and with the backing of the BBC. In its first, unrealised iteration, it was to star Martin Kemp and The Cheeky Girls.

After that I released my own script for publication, in a collection that you can pick up here for your e-reader if you’re so inclined. Or if all you want is a taster, here’s the opening scene.

And for the avoidance of doubt, that other project was neither the Rhys Myers nor the Moffat/Gatiss take on the character, but preceded both by some years. I’ve never seen it; not out of petulance but because it’s impossible for me to give a fair reading to some blameless other people’s hard work after something like this.

Okay, and petulance. Allow me that.