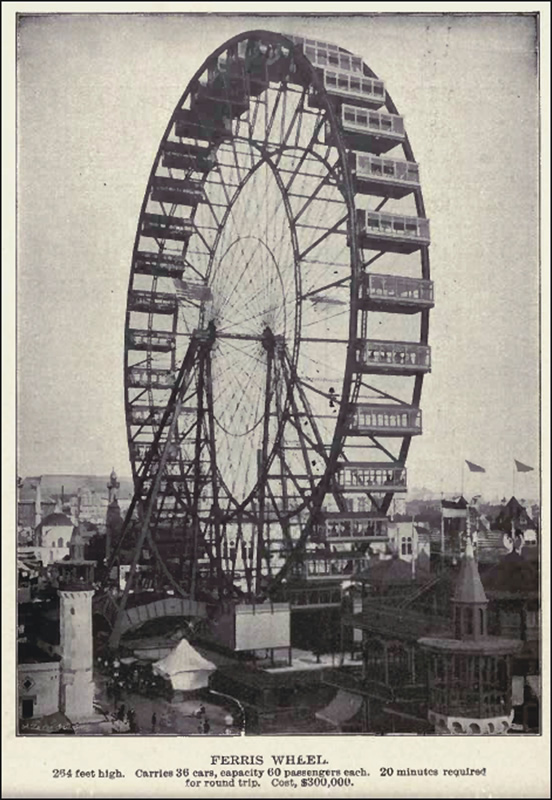

The Devil in the White City is one of my all-time favourite nonfiction reads. Historian Erik Larson counterpoints the planning and staging of the 1893 World’s Fair with the murderous activities of one “Dr H H Holmes”. The fake doctor – real name Herman Webster Mudgett – was a plausible charmer who preyed upon young women drawn to Chicago by the prospect of work and the excitement of big-city life in changing times.

One of the most frequent arguments to be offered in praise of the book is that it ‘reads like a novel’. So it does, and a particularly rich one at that. We look into a world that is not our own, distanced by time, to find a timeless drama of fear and conflict. The historical panorama fascinates but it’s the crime, the crime that drives the tale.

Historical crime. Pick any era, and you’ll find a crime writer working the ground. Margaret Doody’s Aristotle Detective, the Falco novels of Lindsey Davis, Phil Rickman’s Doctor Dee, the Victorian railway detectives of Edward Marston and Andrew Martin (working half a century apart). Alienists, playwrights, and celebrities of the day all take the investigator’s role, with varying degrees of credibility and success. Anthologist Mike Ashley’s collections of historical crime draw together stories from Ancient Egypt to 1930s New York, and just a glance down their contents pages is enough to show that there’s far more to the field than yet another Sherlock pastiche or tale of Jack the Ripper.

For me the stories that work least well are those which impose modern methods or attitudes on their historical context, treating history as little more than a dressing-up box. The best of them recognise that the past is, indeed, another country, where it’s part of the thrill not to feel at home.

When it comes to imaginative creation, historical fiction is a harder act than most to pull off. The rules for the Walter Scott Prize, one of the richest in the field, require that “the majority of the events described take place at least 60 years before the publication of the novel, and therefore stand outside any mature personal experience of the author.”

What does that mean for the story? For the author it means putting in serious work to achieve a sense of authenticity, where nothing can be assumed or taken for granted in the creation of your fictional world. That still leaves plenty of room for the imagination. In skilled hands and with the right attitude, even the most improbable events can be made plausible. Conan Doyle did careful research on his Lost World, and then populated his plateau with believable dinosaurs. Publication of The Lost World in 1912 gave me the springboard for a work of my own, when I was inspired to look into the real lives of its Edwardian subjects. The result was The Bedlam Detective, in which a discredited explorer’s fantasies may hold the key to the murders of young girls on his estate.

I’ve read other ‘true crime historicals’ since The Devil in the White City. Larson’s own Thunderstruck counterpoints the Crippen case with the development of the technology that would play such a big part in its climax, while Howard Blum’s American Lightning juxtaposes the birth of Hollywood with the bombing of the Los Angeles Times offices in 1910. But the balance is an elusive one. It’s a rare dramatic crime that exactly fit the needs of a dramatic narrative.

Which means it’s rare to find the factual history that really does read like a crime novel.

For that, you need a novel.

First published in The Weekly Lizard

One response to “A Criminal History”

Robert Bloch's nonfiction account of Mudgett, published several years after his novel AMERICAN GOTHIC, suggests there is some evidence that his name wasn't actually Mudgett, either. Anthony Boucher's ultraviolet humor comes out in using both that name and Holmes as his other primary pseudonyms…