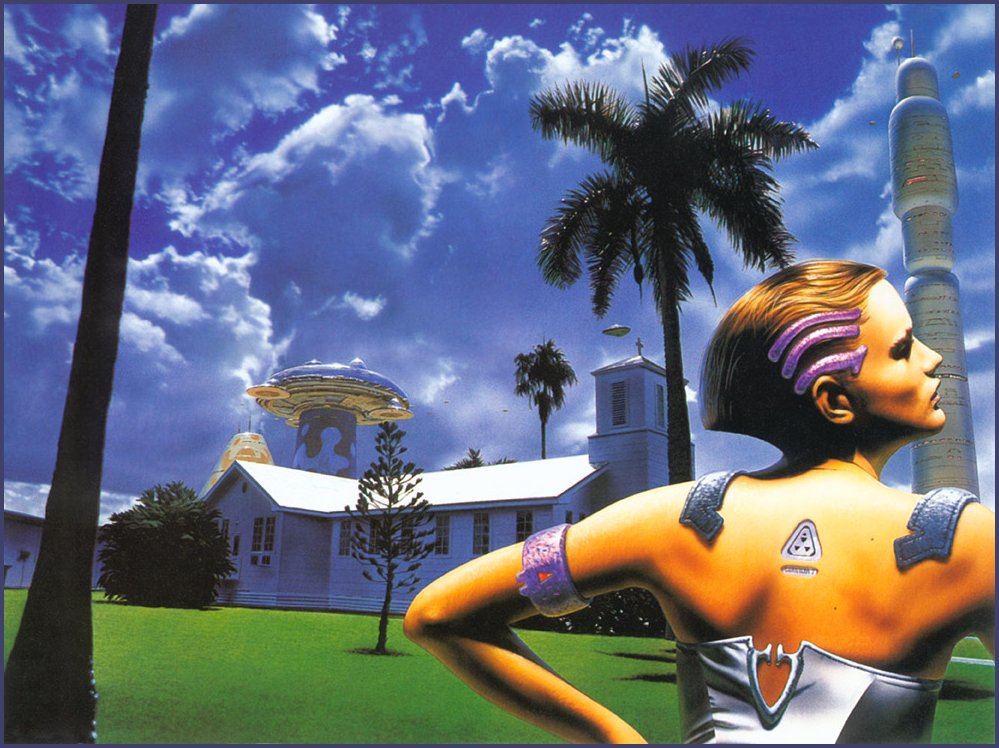

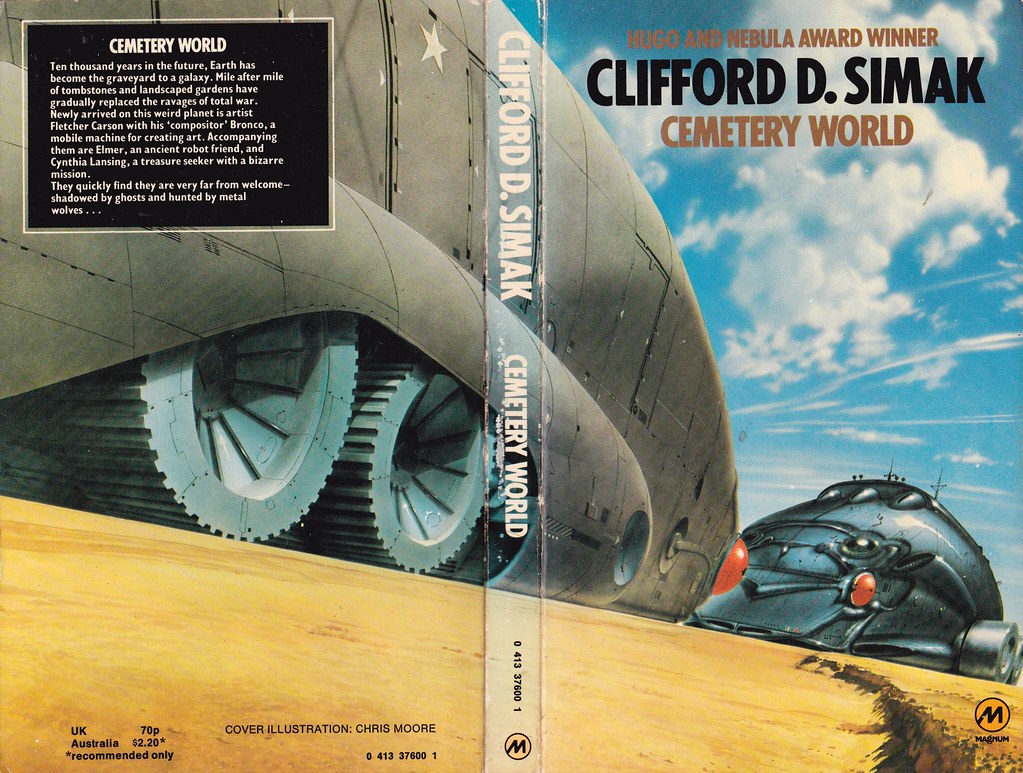

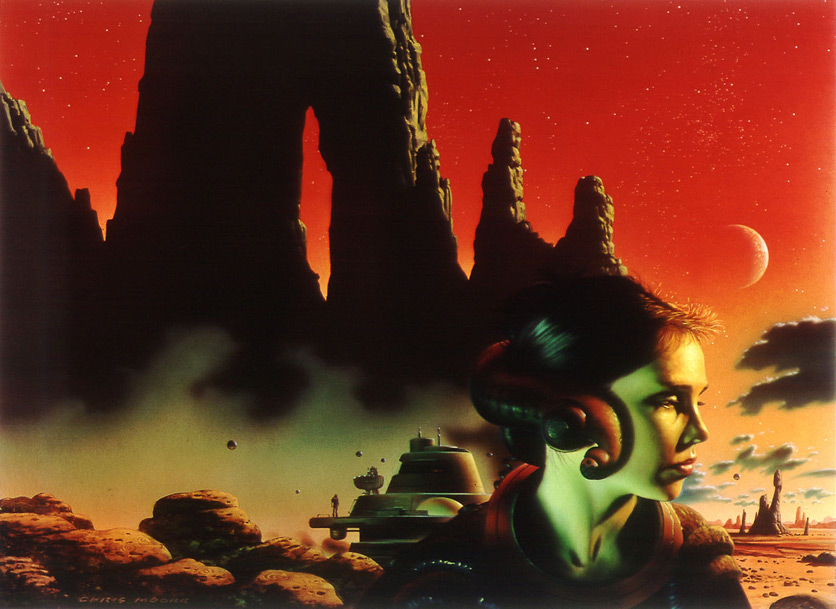

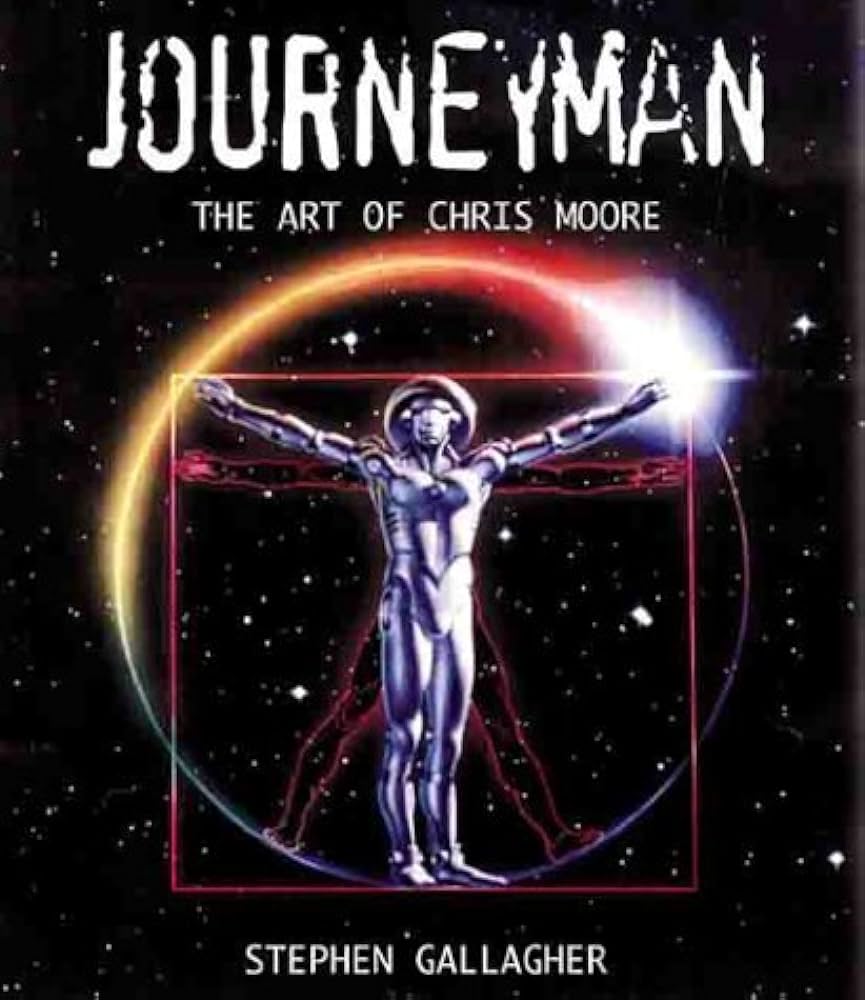

Back in 2006 renowned/esteemed/iconic artist Chris Moore wrote an article on the increasing use of digital tools in the craft of illustration. We’d collaborated on the text of Journeyman, his quality showcase album from art publisher Paper Tiger, and he asked me to cast an editorial eye over the piece before he sent it in. Far from being a Luddite, Chris was among the first to run the new technology alongside the drawing board as an additional professional tool. But already he was beginning to sense the likely impact of these new tools on creativity in the long term.

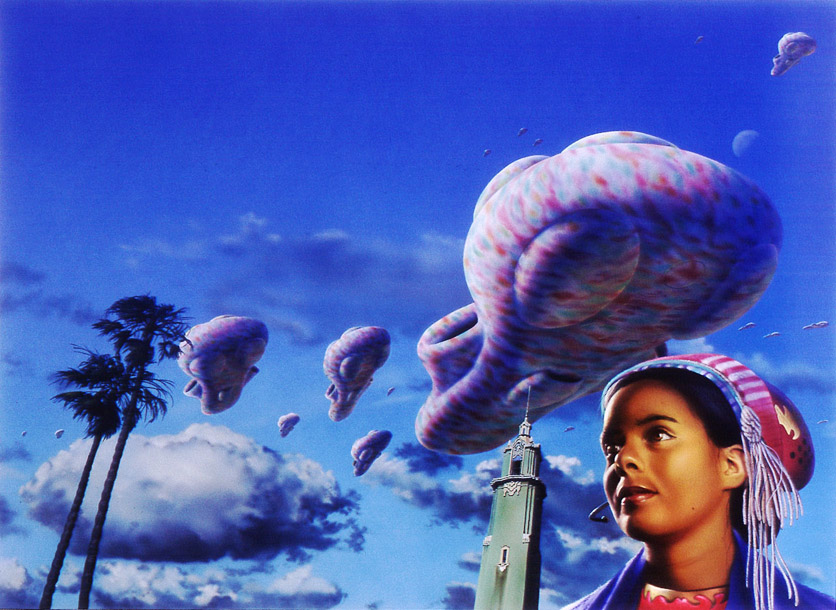

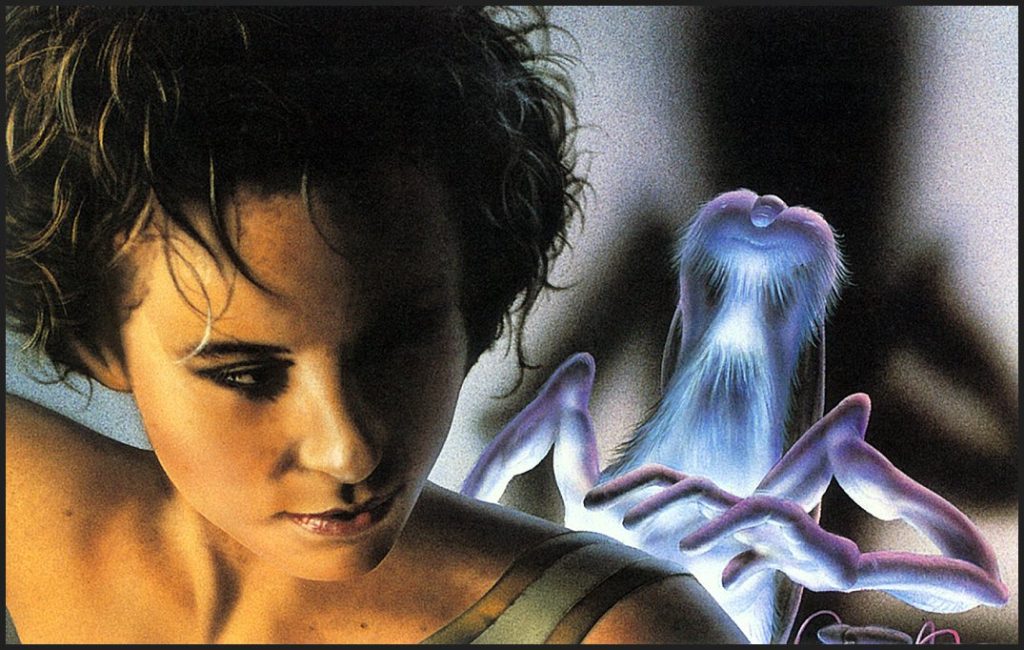

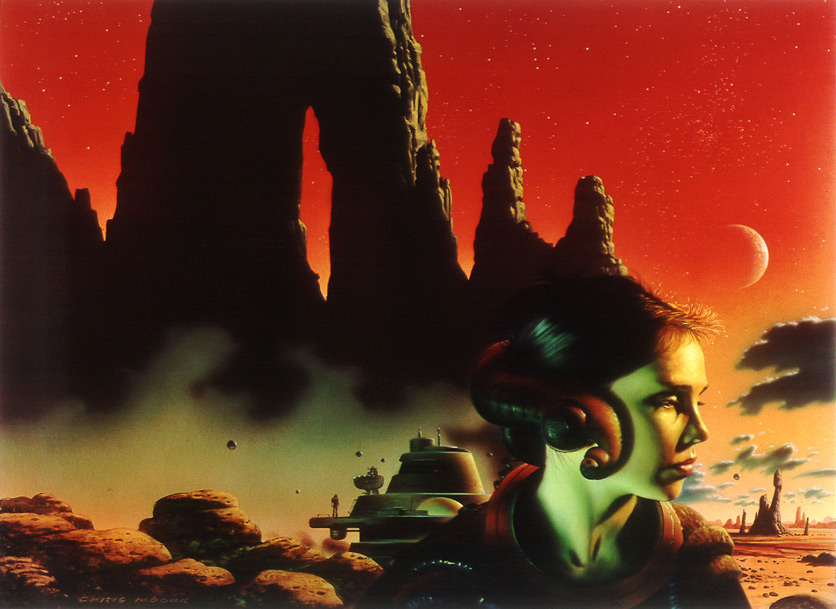

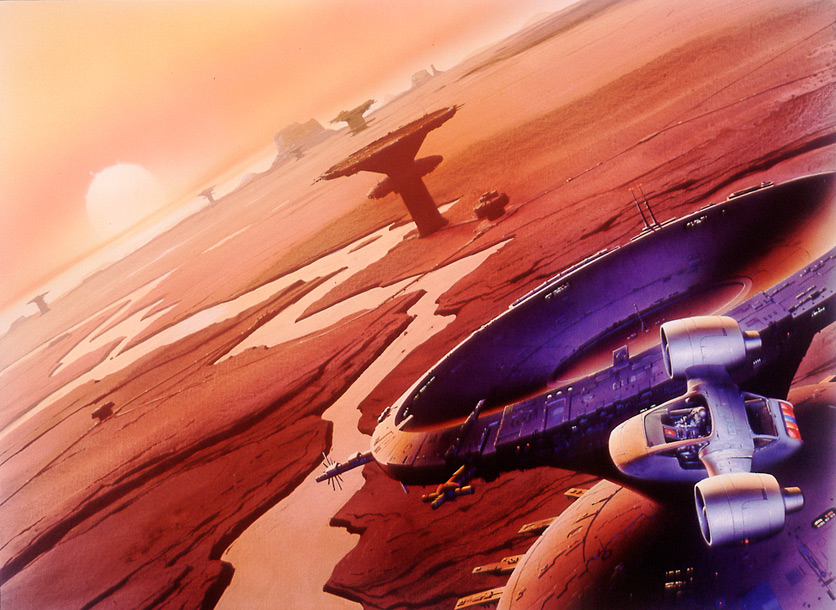

Now that AI has entered the field, these observations seem even more on-point than they were at the time. Along with his cohort Chris Moore is a key figure in a golden age of modern SF illustration. Theirs are the visions that AI now plunders for its product; theirs are the styles that it strives to achieve.

This morning, searching for something unrelated, I came across the original article in my files and read it over again. With Chris’ permission, I’d like to offer it here.

Computer assisted art. I’m all for it. Aren’t I?

I mean, look at my studio. Not the one with the big window and the Northern light and the two drawing boards – these days I hardly seem to spend any time in there. I’m talking about the windowless room underneath it with the Mac and the two monitors where most of my work is now produced. Over the past five years, a significant percentage of my output has been in one digital form or another.

And it’s great. If you can use the software effectively, you can literally achieve anything you want – not just in single digital images but in film and animation as well. All it takes is a computer powerful enough to cut down render times to a minimum, a huge amount of patience to deal with the unreliability of the technology, and the ability to tune out background noise.

I’m not referring to the hum of the cooling fans. Nor to the kids tapping at the door, desperate to get their hands on my work machine to bring it crashing down with the ultimate Grand Theft Auto experience. I’m talking about something unique to the technology of computer assisted art.

You know the noise I mean. That faint, barely audible slurping sound.

The one it makes as it sucks away your soul.

I was recently asked along to University College, London to give a slide show for The Association of Illustrators. My friend Dick Jude was presiding over an event that also involved four other artists: Jim Burns, Fred Gambino, Alan Lee and Dave McKean. All of us had embraced digital technology in one form or another – even Alan Lee, master draughtsman, had succumbed to using Photoshop when working on The Lord of The Rings.

It was a great day for me, sharing a platform with some of my all-time heroes. I showed a mixture of stuff… some of my earlier work, a few more recent paintings, and some digital pieces.

One of the slides was of a landscape on a moonlit night that I’d painted as a birthday present for my wife. I don’t get many opportunities for purely personal work, but it’s something I like to do when I have the time. An extraordinary thing happened. A lady who’d been in the audience came up to me after the talk, and was clearly excited. She said that the moonlit landscape had so much passion in it compared to the computer work that I’d shown. She simply had to tell me. She was so emphatic that I was taken by surprise, and she made me stop and think.

There is no doubt that the technology is here to stay. But I can’t help feeling it’s a shame that the traditional skills of drawing and painting are largely dying out, or being driven out. Most art schools nowadays have banks of computer screens where they once had drawing boards. I suppose that they feel that they’re serving the graphics industry by turning out computer-literate graduates. I think it’s short-sighted – for me, the fundamental skills of drawing and painting are essential to creative expression.

There’s much more to this than a nostalgic longing for ‘the old days’. With paint there’s a tactile quality – you’re literally moulding the image with your hands, and you don’t feel detached from the process by a layer of technology. I like to see paint strokes. Behind a lot of my own work has been the secret hope that the viewer might be amazed by what I had produced using ‘just paint’.

Computers give you more options, more choice, more directions to go in, more facility, more of everything. One may argue that this is a good thing, and in some ways it obviously is. But a person can have too much choice. The real pleasure for me comes from creating something satisfying with the limited materials and resources available. There’s something very personal and thrilling in producing artwork by hand that fits the brief and blows an art director away.

And despite the fact that so much of my output these days involves the building of digital images, I can’t help feeling that there’s something about the process that gets in the way of what I want to do. I can get a high-quality result, but I’m always left with the feeling that I haven’t so much created it as assembled it. And that matters. Most of the illustrators I know put a lot more into their work than is absolutely necessary for the printed image to read, and yet they still do it. Why? I’d guess it’s because they have a pride in what they do. I always see this attitude in the top guys – that good work means satisfying themselves first, and the client second.

As well as bringing changes to working methods, computer technology has wrought a subtle change in the artist/client relationship. Commercial artists have always been under pressure to produce images quickly and to deadlines, and computers have made it possible to deliver work, receive feedback, and make all the changes in less time than it takes a FedEx bike to find the studio.

The downside of this convenience can be that the work leaves your hands in a form that others can very easily alter. H G Wells once wrote that “no passion in the world is equal to the passion to alter someone else’s draft,” and clients are hardly immune to the urge.

As a working illustrator for some 34 years, I’ve become used to people ‘messing around’ with my images. While a lack of control over one’s imagery is often irksome, it goes with the territory and I’ve always seen myself as part of a team, all of us working together to achieve a satisfactory result.

But many of the people who now commission art have spent their entire working lives with computer technology, and have no hesitation in using that technology to get straight to the result they want. One messes with a piece of physical artwork at one’s peril. But in the digital realm, where every element is accessible, and no change is irreversible, and major alterations can be made without any need to call on the original artist’s skill, the opportunity to remake another person’s work is just a mouse click away. This can sometimes demote the artist to the status of a supplier of ‘bits’ for the art director to use in ‘their’ composition, or at best to a producer of images for the art director to change.

The march towards the complete digitisation of everything is now unstoppable. Spectrum Fantasy Art Book started to include a few pieces of digital work in its selections around 1996; by 2006 digital images accounted for around 50% of the featured material, so I guess it’s here to stay. It’s an indication that many artists are moving into this area to get work and that there is a lot of new talent coming up… a computer-savvy generation, using the medium they were born to.

I have heard people say that there is a move back to more traditional ways of working, but I haven’t seen much evidence of it in my corner of our profession. Undoubtedly computers are cleaner than paint or pencil, but I have yet to find that the entire process of creating an image on computer is quicker than in paint. I hear so many of my colleagues saying that their eyesight has really suffered since they began using computers. But maybe that’s just the onset of old age!

I suppose that the real problem I have with computer assisted art lies in the feeling I get when I look at my own examples. It’s as if the pieces coming out of me lack a ‘soul’. There’s something that gets in the way of the personality of my work. It may just be that I can’t handle the software well enough for my demands on myself. But I suspect it’s more the feeling of being one or two steps removed from the ‘meat’ of it.

There’s almost nothing an artist can do that can’t now be replicated using digital tools. It’s as though the guys who write these programs have taken pleasure in finding a digital way of doing everything. If it can be done by hand, it can be reproduced by software… water, foliage, mountains, reflections and stars can be generated without human effort. Any line, any stroke, any technique can be emulated to perfection.

And that’s the problem. Because soon a generation will pass. And with it will pass the ability to create those lines, strokes and techniques because, let’s face it, those who follow will have been trained in other ways.

Something will have been lost, perhaps forever.

The skills will be gone, and only the mimicry will remain.

© Chris Moore. First published in Paint or Pixel: The Digital Divide in Illustration Art, ed Jane Frank

All art by Chris Moore. #8 a digital painting. None using AI.