Okay, it’s a leap, but talking about Pan Books in the Sam Peffer post reminded me of something that’s all but disappeared with the advent of widescreen TVs; the ‘panning and scanning’ of movie prints for TV broadcast.

We’ve reached the point where the 4×3 Academy Ratio TV set is only ever seen as a prop in period dramas, but for over fifty years it was the standard. All programming was made in that almost-square format; anything that wasn’t had to be fiddled to fit.

In the early days of widescreen cinema, studios saw TV as the enemy. Going bigger, wider, and more spectacular was the response, and it’s said that some would even go out of their way to ensure that their images would play badly on the small screen. It was a shortsighted view; TV was to extend the earning potential of any feature way beyond its original release window.

Regular readers of the blog will know that one of my earliest jobs was in the Presentation Department of a commercial TV company. On the rare occasions when we broadcast a print in full widescreen with ‘black bars’ above and below the image (aka ‘letterboxing’), the Duty Officer’s phone would ring off the hook with viewers’ complaints. Even when our Telecine engineers attempted a compromise, zooming slightly to lose the edges of the image and minimise the letterboxing, viewers were unhappy. It was like they wanted their screens completely filled up with picture on principle.

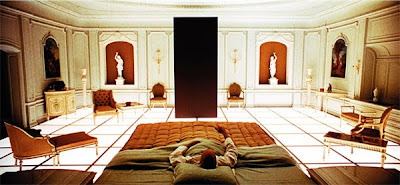

Letterboxing of films was rare on ITV. You’d find it more often on BBC2 or Channel 4, in the arthouse slots. Mostly we’d be provided by distributors with special TV prints of studio features, already adjusted for the shape of the screen by the process known as panning and scanning. The prints came with every scene reframed and optimised for TV. This involved losing anything up to one-third of the picture detail, along with all original sense of composition.

Panning and scanning could go way beyond the cranking of a frame to the left or right to squeeze the action in – a small section of a scene could be selected and enlarged to make a closeup from a medium shot, for example. I recall a scene which, in the original, was a single long take of two people talking. The telecine operator had reframed each person in a separate, enlarged closeup and then cut back and forth between them, playing editor. Didn’t match, didn’t work, looked appalling. But it used to be quite common.

Those calls of complaint seemed to persuade my bosses that no one out there really cared about quality. Or at least that they only cared for a Philistine’s version of it – fill up my screen, crank up the colour until every face is orange, and nothing in Black & White, thanks very much. It was an assumption that persisted well into the Home Entertainment revolution, despite the fact that the revolution was driven – as all revolutions are – by a desire for something better. One of the great annoyances of being an early adopter of widescreen TV was that of finding that the DVD you’d just paid top dollar for had been mastered from one of those 4×3 television prints.

(Ipcress File, I’m looking at you. A crappy Carlton release which I’ve since upgraded to Network DVD’s superior issue.)

Now all TVs are 16×9 and while that ratio doesn’t correspond exactly to any theatrical format, it lends itself to less noticeable compromises. When I began shooting my own stuff the viewfinder on the film camera included an element with the ‘safety zones’ of the different viewing formats etched into the glass, so that the operator could ensure that whatever the composition, the essential information would fall within the frame and the shot would always make some kind of sense. Now such information’s more commonly found on the video assist monitor. If you see a movie where you can make out the edges of the sets, or the microphone dips into shot, then it’s probably not being shown in the ratio for which the operator framed it.

In Presentation now, everything’s been turned on its head. It’s old (‘vintage’) 4×3 material that causes the negative audience reaction. People shy away from 4×3 the way they shy away from Black & White.

In this case the choice is between seeing vertical black bars to either side of the image (pillarboxing) or zooming to fill the frame, losing the top and bottom of the picture and, once again, bolloxing the composition. The results are just as ugly as Pan and Scan – uglier, if anything, with exaggerated grain, noise, and visual clutter in images that were low-resolution to begin with.

Then there are those directors who shoot a digital frame, then add letterboxing to mimic a Panavision effect on a 16×9 screen.

To which one can only say, Dream on.

9 responses to “Pan and Scan”

I remember in the early part of the 1990s, during one edition of Moving Pictures – the movie programme on Saturday nights – it had a report on whether, during filming, directors kept an eye on framing their scenes, knowing full well that when their movie eventually arrived on television it would be subjected to the cruelties of pan & scan.

The interviewer talked to Michael Mann, pointing to the scene in The Last of the Mohicans where troops line up outside Fort William Henry on the extreme left and right of the frame so the '4:3 area' directly in the middle was torn up battlefield devoid of an soldiers. Mann's response was, if I remember rightly, similar to Hugh Hudson's “Fuck the critics!” in Alan Parker's A Turnip Head's Guide to the British Cinema, with him replying, “Fuck television!”

As a young viewer I suppose I didn't know any better until films I had seen at “the pictures” started appearing on television and I'd notice stuff missing or the “camera” sliding left and right when before it had remained static. Then, because of where the opening credits were placed within the frame, films broadcast on television would begin letterboxed, at least until the final 'directed by' credit. At that point the black bars would sadly rise/lower out of frame, “zooming in” on the image on screen. Or – even worse – if the director's credit appeared during the beginning of a scene we would be teased with the idea that we were going to have the film in the correct ratio… until it cut to the next camera angle and: Boom! Full screen. Dammit!

At least Moving Pictures, and The Film Club before it, would be followed by a film or two show in the proper aspect ratio. That might have been when films on television started to got the respect they deserved. Or did Channel 4 show films in the correct ratio from the get go?

Pan and scan was bad, but worse were the occasions when during, say, a dialogue exchange between characters on the extremes of frame, the decision was made to chop the film frame into two rather than going back and forth and back and forth, as if someone was filming a ping–pong match.

The worst offender was ITV broadcasting Jaws and especially the scene where Brody, having been slapped by Alex Kintner's mother, sits silently at the dinner table with his young son. Brody has his back to the left side of the frame, the son has his back close to the right side and I suppose it's not difficult to cut back and forth from one to the other.

The only problem was that Roy Scheider had his right arm stretched out on the table so when Brody is on screen you see his right arm from shoulder to wrist. Then when the son is on screen, on the left hand side of the TV frame is Brody's wrist and hand. So it looked like the film was directed by a complete goat–boy. Oh dear!

I'm finding it interesting now to see how 4:3 material is handled on the various channels. Do the various broadcasters put something smart through the signal to the smart televisions? Some old shows on certain channels automatically turn up on my nice set in the correct ratio with black bars on the side. Other old shows on other new channels come in at 16:9 and I have to change the ratio rather than watch everyone shorter and fatter than usual. Catching the odd repeat of The Avengers on the awful True Entertainment channel, the picture looks like it has been accidentally run through some process twice, making everyone especially tall and thin, which means I have to make the image 14:9 to correct it.

It's a shame that because of the modern aversion to 4:3 they have had to go ahead and reformat The Wire – http://davidsimon.com/the-wire-hd-with-videos/

Oh dear.

My box set of The Shield has early episodes in what used to be called 'full frame', switching to widescreen later. The season 1 DVD set that I had in LA was widescreen, so the UK and US releases differ.

I've seen interviews with Shawn Ryan where he says that all the episodes were shot on 16mm with an 'open frame' and edited in that format, which is how he'd prefer them to be seen. But why you'd shoot in a format that your broadcaster won't countenance, I have no idea.

The remastered HD original Star Trek series is being shown on CBS Action in the UK panned-and-tilted. Bleh. Managed to pick up the Blu Ray from Cex the other day, so I'm looking forward to finally seeing them again.

Worse though, the entire UK DVD set of Buffy The Vampire Slayer have been mastered in 16:9 rather than 4:3, so there's actually no way of watching it properly here at the moment. It's so ugly I had to import the US DVD set, which has the show in the correct aspect ratio.

I have a small number of older DVDs – I think Brosnan-version Thomas Crown Affair is one of them – that had the movie in fullframe on one side of the disc and widescreen on the other. I think they were referred to unofficially as 'flippers'.

Because there was no label I would invariably put them into the player wrong-side-up.

I have the first three seasons of The Shield still boxed away somewhere and I'm sure they were in 16:9. Should watch them again when I have the chance.

In terms of a 4:3 broadcast / 16:9 home entertainment debacle that really does the viewer absolutely no favours, well over a decade back I was sent a review copy of Babylon 5 season 2 on DVD. The show had initially been broadcast “full frame” (4:3) during the 1990s but Straczynski had repeatedly rabbited on about wanting to see it eventually reformatted in the wider aspect ratio.

That's no problem with the live action obviously shot on film stock. But it's going to be a serious issue if he signs off on the CGI shots being rendered in 4:3. Letting that happen is not exactly what I would call forward thinking. Even if the numerous builds had been archived the scenes would have to be re-animated and re-rendered. Obviously not the thing Warner Home Video would fork out for.

It meant that while watching the review copy, I couldn't fail to notice the quality was just all over the shop. To get scenes involving any CGI elements – whether set in space or inside the space station – in a 16:9 format it looked like some maroon had parked themselves in a post–production suite, loaded up the existing 4:3 footage, and simply zoomed in. And to hell with the pixelation and aliasing, the softening of the live action!

There was another approach sometimes taken by the BBC when I was a kid (c. 1970): rather than pan/scan or letterbox, they'd do a vertical stretch-o-vision to fill the frame. Often this only lasted until the credits ended, but I remember several films with unnaturally tall, thin characters throughout.

The masking of prestige dramas into extra-wide (Cucumber was a recent offender) is very annoying. Letter boxing of films doesn't bother me – I tune it out after a minute or two – but I do think television programmes should be television-shaped.

rather than pan/scan or letterbox, they'd do a vertical stretch-o-vision to fill the frame

There's always the possibility that the telecine engineer had set up wrong parameters and gone home early… like the notorious C4 screening of Tarkovsky's Stalker where the shift from monochrome to colour never happened because the operator only checked the first few minutes, switched off the colourburst on his machine, and knocked off for the night.

@Paul

I remember at the time JMS talking about the effects work for Babylon 5.

The plan was always to shoot framed for 16:9 4:3 safe, and save the digital assets. They'd render the CGI in 4:3 for the television showing to save money, and then when the 16:9 release happened simply render new CGI shots for it.

They lost the assets, and it's never sold well enough to be worth remastering the CGI from scratch.

@Stephen

I must have watched that showing. Because WHAT DO YOU MEAN STALKER IS IN COLOUR!?!?!?

It's monochrome up to the point where they enter the Zone and then…

https://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_detailpage&v=JYEfJhkPK7o#t=2207