First published as a guest editorial in Kimota magazine, 2014

I couldn’t be an editor. There are so many stories.

I don’t mean the kind of stories an editor actually looks for. I mean some of the stuff they have to deal with. Stories of writers, invariably new to the game, demanding that you sign an NDA before reading. Of writers believing that the act of submission entitles them to free feedback. Writers who argue with feedback when they get it. Writers whose angry response to rejection is to point out all those excellent qualities in the work that you, the stupid editor, clearly missed.

If you write, you’re going to get more passes than prizes. Fact of life. Being rejected calls for a thick skin, while creation is a business for the thin-skinned… I don’t know how you can ever successfully reconcile the two. I’ve been in this game for a while, and I can’t say I’ve ever managed it.

I suppose I’ve learned a little perspective, though. An inexperienced producer who optioned one of my early novels taught me a lesson that he surely never intended. Every time the script came back from a distributor or production company with a polite pass, he’d take their given reason as a signal to rewrite and resubmit. In his mind that had to guarantee acceptance the second time around, all obstacles removed. Thirteen drafts later, the once-tight script was a shapeless mess. And I dare say that everyone in town had him marked down as an idiot.

So that’s not how you do it.

And feedback – it’s not an editor’s job to be a writing coach although some, Kimota‘s Graeme Hurry amongst them, go beyond the call of duty. In such cases, take it with grace.

But those writers and their NDA letters. Non-disclosure agreements, legally binding documents that swear the signer to secrecy. Paranoid over their copyright and convinced that the world is out to steal their ideas. They’re the reason so many publishers and production companies won’t look at unagented submissions. They’ve learned the hard way.

I once complained to my agent that the premise of an ITV drama was the same as that of a project I’d written on spec and submitted a couple of years before. There were enough detailed coincidences to fuel suspicion that someone in the notes process had at least helped to steer it with my story in mind.

My agent talked me through the unlikelihood of this. She knew many of the people involved. She knew something of the deals and the gestation of the project. I won’t rehash her advice but I’ll summarise the overall lesson, which was, in essence, “Grow up, Steve.”

The fact is, no one’s out to steal your ideas. They’re not that great a commodity. Any value in them is execution-dependent. An idea can’t be copyrighted, only the form that you put it into. That’s why plagiarism lawsuits have to be so closely-argued, showing the conscious reproduction of detail after defining detail, and why they so rarely succeed. Mostly they’re settled out of court, to save the expense of dragging out the arguments.

There’s one going on as I write. If you’re not familiar with Orphan Black, a Canadian series made for BBC America, you’re missing one of the better pieces of TVSF of recent years. It made a breakout star of Tatiana Maslany, who plays several cloned versions of a single biological entity with dazzling technique. The springboard for the story is an incident in which streetwise lowlife Sarah Manning witnesses a train suicide by a woman who resembles her exactly; after opportunistically stepping into the woman’s identity, she finds herself to be one of a number of human clones in the process of trying to connect and uncover the secret behind their existence.

The lawsuit – the full legal submission for which can be found online – is from Stephen Hendricks, writer of a spec screenplay called Double, Double that he submitted to Canadian producers Temple Films a decade ago. The suit now alleges a systematic conspiracy to exploit his material while depriving him of copyright, asserting that the show contains “the same, unusual core copyrightable expression as (his) Screenplay; i.e. the clandestine development of clones and the resulting journey of the protagonist to discover her origins.”

I can sympathise with Hendricks. I can imagine what it must feel like to pitch a show about clones to a company, have them pass on it, and then see them make a successful show about clones in which you see so much of your own thinking reflected. I’d feel an inevitable sense of outrage too. I might even be moved to sue.

But I suspect a struggle lies ahead. That “core copyrightable expression” – the clandestine development of clones and the resulting journey of the protagonist to discover her origins – is little more than a common SF trope framed in a classic hero’s-journey story arc. It’ll need some pretty damning evidence from the execution to make the case for stolen originality stick.

The list of examples is impressively long. But reading them – “both protagonists begin the story not realizing they are anything other than who they are told and therefore think they are… both protagonists become resourceful… both protagonists become capable detectives” – it’s hard not to think that this pretty much the way anyone would develop the same premise in a science-based conspiracy thriller.

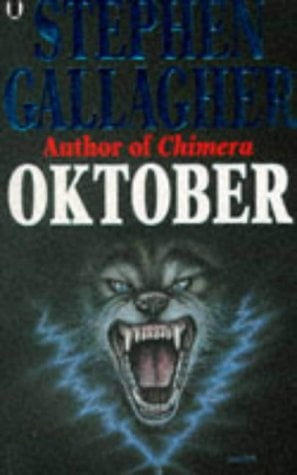

I’ve done a few of those in my time, from Chimera to Silent Witness. So I tried a bit of a thought experiment.

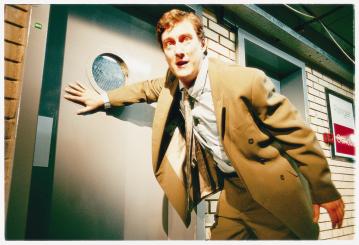

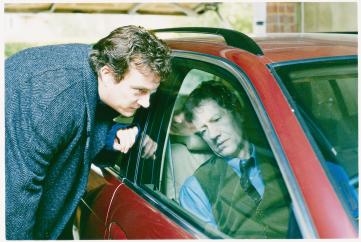

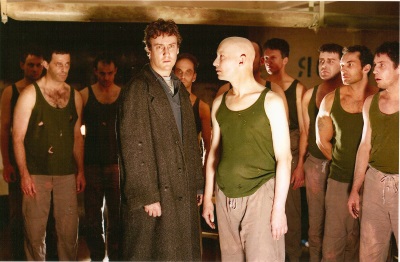

In the 80s I wrote a novel called Oktober, adapted for TV in the late 90s. No cloning, but an unwitting hero who finds himself to be the human subject in a clandestine science project and embarks on an investigation into the truth behind it. He discovers that some of those close to him are actually agents of the organisation behind his plight. He has to go on the run. In the process he’s transformed from an inoffensive schoolteacher into a fast-thinking survivor. The organisation behind the conspiracy, headed by the cold-hearted and ambitious Rochelle Genoud, sees him as valuable property to be captured and exploited. There’s extra danger in the form of a rogue apparatchik, doing the boss’s bidding but going steadily out of control, who’ll strike down anyone in his way.

Here’s what I found. Take out the cloning and about 80% of the lawsuit’s “wholly original elements and key ideas” apply equally to Oktober, including:

“Both Double Double and Orphan Black are dark. Both protagonists go through plot and character points that are bewildering, restless, determined, horrific and sad. There is a general mood of fear and dread in both. The element of solitude is present in both — being alone against it all, despite having friends, family and mentors. Both Double Double and Orphan Black are fast paced action thrillers that quickly become a frantic race for survival and search for the truth while avoiding the pursuing authorities and antagonists.”

Am I reaching for a lawyer? Of course not. Because all this stuff is common craft and not the unique DNA of any one piece. I feel Stephen Hendricks’ pain but I don’t much rate his chances.

Writing’s hard enough. We can lay the paranoia aside. The industry is not out to steal your ideas. Why steal your work when they can buy it cheap, kick you off the project, and go on to trash it with impunity?

That’s the Hollywood way.