I see that Patrick Barlow’s energetic stage adaptation of The 39 Steps is about to begin a national tour, in a production directed by Maria Aitken (whom I met once at the Hay festival; I was on a panel with her husband Patrick McGrath and was happy to be introduced). The original Criterion Theatre production and subsequent Broadway transfer starred Murder Rooms’ Charles Edwards as Richard Hannay.

Anyway…

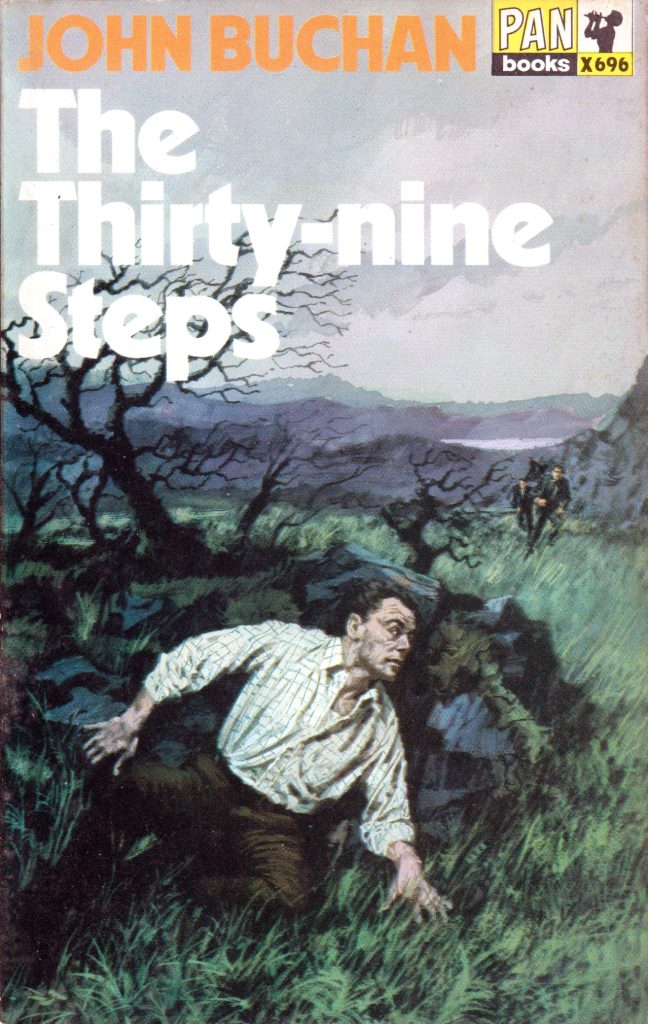

The news took me back 20 years or more to a moment when I pitched a new adaptation of the John Buchan novel. In turn this sent me to the archive, my personal museum of the unmade. What I remember as a short note is actually a 4-page riff on the book and what to do with it. No one had asked for this, it was just me taking a shot. One of many… hard for me to believe how much spare brain energy I could summon back then. But I reckon I can at least get a double blog post out of it now.

Beware; never really intended for public view, what follows is neither reverent nor respectful…

Re-reading the book confirms my remembered impressions of it. Possessed of a terrific narrative velocity, it falls apart to an unmemorable end. But the sheer verve of the storytelling persuades you to overlook this and its other faults, chief among which is the fact that the narrative doesn’t hold up under any but the most uncritical scrutiny.

The ride is all. Buchan’s greatest strengths are in the first-person telling, in the locales and the atmosphere (especially the open countryside, which is marvellously done), and in the constant sense of high adrenaline in the story’s forward progress. This is basically a prisoner-on-the-run story, a manhunt from the point of view of the quarry, the twist being that the fugitive has the moral high ground. It’s about survival, it’s about turning the tables, it’s about prevailing.

The glue that holds it together is Buchan’s characterisation of Hannay. He takes the stock Edwardian clubman figure, with his London rooms and his valet and his private income and colonial experience and his sporting values, and gives him a believable voice. It’s an impressive achievement, even more so when you note how little in the way of characterisation he gives to any of the other figures in the tale (with the possible exception of Scudder, who doesn’t stay around for too long). These are almost without exception the stock types of clubman’s fiction, defined by entirely by their rank or their class. They’re given minimal setting-up and many of them don’t even get names. People are recognised as Good Sorts and Bad Sorts without any need for qualification or demonstration.

Buchan has obviously sensed from a distance the arc that he wants to achieve, starting in the bustle of the city, looping out across the far wide country, finding what looks like a haven, only to discover with a rug from under your feet feeling that, rather than make his way to safety, he’s made his way to the heart of the conspiracy. And then a final act in which our hero, with his good character restored by now, is at the head of the column of the forces of right in the final showdown.

It’s a strong and instinctively satisfying structure. But there are huge pitfalls in putting it straight onto the screen in the way that Buchan wrote it. He falsifies process and reality at every turn, short-cutting his way to the action. In a way, that falsification isn’t so much a flaw in the book as the schtick that makes the book work. It’s like the logic of a children’s story, the empowering, wish-fulfilment kind, the kind where the Chief of Police begs eleven-year-old Johnny Atom to look into the case that has his best men baffled.

It was ridiculous of me to take charge of the business like this, but they didn’t seem to mind, and after all I had been in the show from the start. Besides, I was used to rough jobs, and these eminent gentlemen were too clever not to see it… “I for one,” he said, “am content to leave the matter in Mr Hannay’s hands.”

The challenge facing the adapter, I would suggest, is that of making the story work for grownups.

It’s a story completely without women, save the odd kindly crofter’s wife speaking in an impenetrable music-hall brogue. Julia Czechchenyi gets a promising early mention but, apart from her name providing the key to Scudder’s notebook cypher, Buchan seems to mislay her invitation. My antennae say that when he started out, he had a vague idea that she’d play a part but then went ahead with the story and found no place for her in the execution of it. What he’d have made of her, is hard to say… more Mata Hari than helpless rescuee, perhaps.

I’m convinced that he didn’t pre-plan the narrative to any great degree. I think that’s the key to the looseness and breeziness of the writing, the price for which is the little range of dissatisfactions you’re left with at the end. It’s a bit like realising that you’ve been entrusting your education to a teacher who’s only two chapters ahead of you in the textbook. You don’t ask searching questions. The edifice collapses if you do.

The Charles Bennett screenplay took the arc or the framework and essentially laid a screwball romantic comedy over it. Comparing book to film is a bit like watching Michael Frayn’s NOISES OFF onstage… the old stuff over there and the new stuff over here, both quite different in character but with just the thickness of a canvas flat to separate them.

The Bennett version makes a great movie out of the material. It zips along, it makes sense, it satisfies, it entertains. Its key and memorable moments – the handcuffs, the Forth bridge, Mr Memory – are all new work. As well as being one of the best Hitchcocks it’s the template for all the other man-on-the-run Hitchcocks and hundreds of other wronged-man movies as well, including the Ralph Thomas remake which was almost scene-for-scene. My memories there are of an engaging Kenneth More performance (always good news onscreen), some dodgy back-projection, and some very two-dimensional staging… all adding up to a pale clone that never succeeded in being its own thing.

As for the plot arc of the Don Sharp/Robert Powell version, I’ve little memory of that at all apart from the obvious hanging-from-Big Ben image. According to Maltin, it’s a return to the book. But according to online reviews it has Powell handcuffed to Karen Dotrice overnight, so it obviously mines Bennett as well.

I wouldn’t be inclined to look too closely at any of the three versions until after I’d given thorough thought to an angle of attack of my own. I think it’s essential to get a handle on that before I let in the noise.

To be continued