Continuing the adaptation memo from Part One, this second part is the ‘what I’d do with it’ section. I teamed with producer Archie Tait and I imagine we pitched it to the usual suspects, of whom there were a very small number back then… maybe half a dozen people or fewer with actual commissioning power, and everyone in the UK TV business trying to guess and anticipate their needs and tastes. Which usually amounted to, “Fresh ideas and no more crime.” So you’d take that to heart and work on your more radical stuff, only to open a copy of Broadcast and read of a slew of new crime commissions.

Anyway…

Some initial thoughts:

Period. The novel was set on the eve of the First World War but at least one of the adaptations moved it to the second. It seems to me that we have two choices; we either stick to the period of the book or we take the radical line and make it present-day.

In favour of sticking to the period of the book: the political situation of the time is distant, safe, and the consequences of spy action are both real and known. Communications were such that Scotland genuinely was a world away from London. The journey between the two feels epic, the landscape sufficiently wild to be mythic. Then there’s all the lovely narrative impedimenta of the time – the steam trains, the costumes, the cars, the overall period mise-en-scene.

I’m also mindful of the simple fact that when you adapt a book, you should do your best to honour it and not simply plunder it.

The advantage of setting it in the present day: simply that it would be an opportunity to rethink the whole thing into a smart and supercharged modern thriller. Richard Hannay is the Great-Uncle of James Bond (I’d call him the grandfather, but I’m not entirely sure that in Buchan’s version of him he’d know what to do with a woman) and THE THIRTY-NINE STEPS is the direct ancestor of the frills-free suspense narrative typified by THE FUGITIVE and 24.

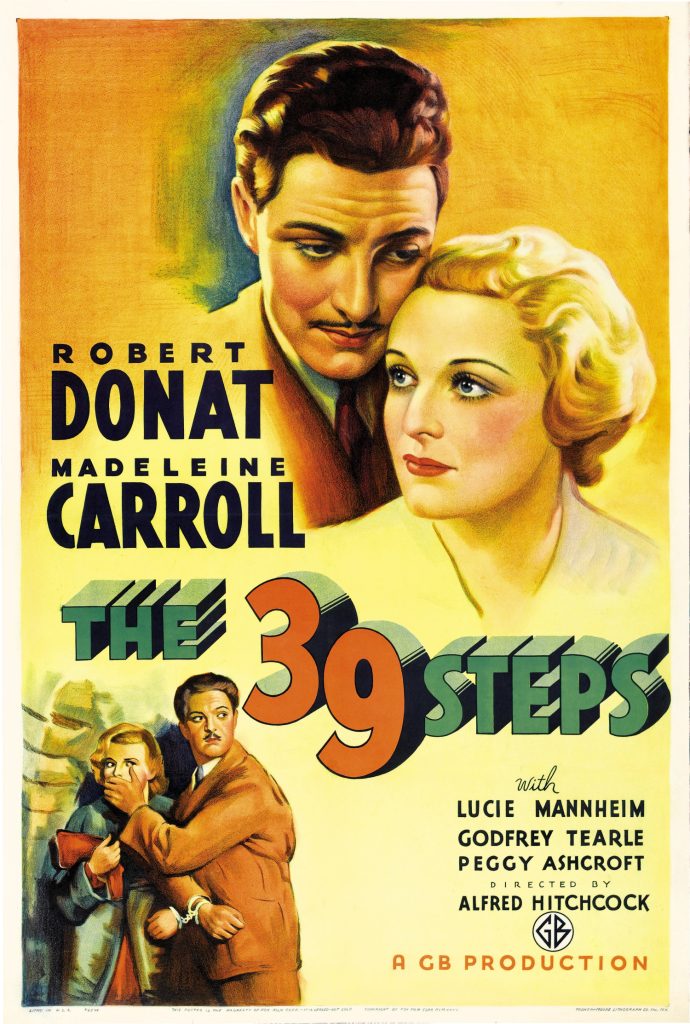

Given that the Hitchcock/Bennett version is always going to be considered as definitive, an updating would free us to stand on our own feet. Sure, one could just go ahead and remake the Hitchcock for a new generation not only unfamilar with the original but unwilling even to look at it… as far as they’re concerned, black and white classics are as inaccessible as foreign-language movies. But… Hitchcock’s Hitchcock. Anyone who’d be happy to tackle remaking him could be exactly the wrong person to be entrusted with the job.

On the matter of period, I see arguments both ways. By no means the least of them hinges on whether broadcasters are in or out of love with period drama this week. Also, a modern-dress version’s never been done. It’s a genuine reason for a new outing.

A new version should respect the arc of the material, create new ‘key and memorable moments’ of its own, and nod to Bennet.

Structurally I’d tidy up the opening, get rid of the misleading false conspiracy stuff that is later replaced by all-new information from the decoding of the notebook. I’d preserve Buchan’s arc but I wouldn’t preserve his plotting. I’d look for the incidents and the narrative beats that he so blithely skips over. Much as we want to get Hannay to Scotland, we need a non-capricious and compelling reason to send him up there.

Less ‘our hero decides to…’ and more ‘our hero has no choice but to…’.

Perhaps the visiting dignitary, Karolides or whoever, whose assassination is scheduled to start the war, is coming in for a peace conference that’s being hosted on some vast Scottish estate, the laird of which is a high-establishment figure and the one man whom Hannay thinks he can trust to hear his tale. He fights his way through to his destination, only to find that he’s entered the lair of the conspiracy’s leader. So when he escapes and goes on his final-act run it’s with his problems doubled, not solved.

(To my mind, complicity of the British establishment with the people’s enemies found its most chilling expression in the Duke of Windsor’s readiness to retake the crown if the Nazis won in WWII).

(And if it’s a contemporary version, the threat doesn’t necessarily have to be war with Britain. In a post-nuclear age, war between any two major nations threatens us all).

Hannay hurtles down to London, knowing that Plan B is to kill Karolides anywhere on British soil since the main plan has been foiled. In the final act of the novel, Buchan has Hannay restored to official credibility. To my mind, this ends the fun too early. The plot starts to freewheel and lose energy just when it ought to be picking up speed and pedalling hard for the finish. My instinct would be to keep him on the run, perhaps with one dedicated policeman on his trail who’s now starting to see what he’s trying to achieve, and who a) enables Hannay in his conclusive heroic act, and b) provides us with the reassurance that Hannay’s actions will no longer be misunderstood and all will be explained. This final scene should be a will-he won’t-he showdown in which Hannay foils the assassination. This conclusion isn’t in the book, but I’d consider it entirely justified on the grounds that the book promises it, but never delivers.

I’d work with more attention to character, particularly those of the pursuing enemies, and I’d look to create a strong female role for the elusive Julia Czechchenyi. Buchan doesn’t give us much about her, but maybe enough to justify her development as an agent inside the enemy’s camp.

Final thought: Richard Hannay, the series. Just in case that’s what it takes to make it all feel more saleable. Probably all-new adventures, as I imagine the various copyrights of the other Hannay books reside elsewhere.

© Stephen Gallagher 2002